John Michael Hayes

Hitchcock's Most Frequent Writing Collaborator in Hollywood

In

a career that spanned more than forty years, beginning with radio, the

movies, and then television, the name John Michael Hayes has become

synonymous with quality. Having produced a body of work that resulted

in two Academy Award nominations, three nominations for awards by the

Writers' Guild of America, and the WGA's Screen Laurel Award, Hayes

amassed not only an impressive list of credits, but a reputation for

writing solidly constructed screenplays, which were prized for their

unique blend of sophisticated repartee and colloquial banter.

In

a career that spanned more than forty years, beginning with radio, the

movies, and then television, the name John Michael Hayes has become

synonymous with quality. Having produced a body of work that resulted

in two Academy Award nominations, three nominations for awards by the

Writers' Guild of America, and the WGA's Screen Laurel Award, Hayes

amassed not only an impressive list of credits, but a reputation for

writing solidly constructed screenplays, which were prized for their

unique blend of sophisticated repartee and colloquial banter.

John Michael Hayes was born on May 11, 1919, in Worcester, Massachusetts. His father had been a song-and-dance performer in vaudeville before starting a family, and proudly passed on a bit of the show business in his blood to his middle child and only son. As a boy Hayes spent a good deal of time out of school from the second grade through the fifth, suffering a series of illnesses. He began his own literary education though, reading whatever books and magazines he could obtain. By the age of nine, John Michael Hayes knew that he wanted to be a writer.

During the early 1930s, the Hayes family relocated a number of times, from Detroit, Michigan to State Line, New Hampshire and back to Worcester, Massachusetts, wherever the elder Hayes could get work. During this time, Hayes first tried his hand at writing, joining the staff of a school newspaper. By the age of sixteen, he had become editor of a Boy Scout weekly, and soon after was hired as a cub reporter for the Worcester Telegram.

Eventually Hayes became interested in radio and put his editing and feature writing skills to work at small radio stations in northern Massachusetts, where he earned enough money to enroll at Massachusetts State College - later the University of Massachusetts - in Amherst. where he majored in English and continued pursuing his interest in radio.

Following an internship with a radio station in Ohio, Hayes accepted a position as editor of daytime serials for Proctor and Gamble. When he was drafted into the Army during World War II, Hayes put the years spent learning his father's vaudeville routines to work, writing and performing in stage shows to entertain the troops.

After the war Hayes embarked on a career as a radio writer in Hollywood, where he quickly found work writing for a variety of CBS shows such as The Whistler and Twelve Players. His stay in Hollywood was cut short though, when he was stricken with a severe case of rheumatoid arthritis. After nearly eighteen months in a veterans hospital, Hayes hitchhiked from Massachusetts to California where he was put back to work at CBS to write a new show for Lucielle Ball called My Favorite Husband. He never looked back.

Specializing in comedy and suspense, Hayes turned out expert scripts for many popular series, including Amos and Andy, Yours Truly Johnny Dollar, Alias Jane Doe, Suspense and Richard Diamond, Private Detective. Among the most successful of Hayes's radio shows was The Adventures of Sam Spade, which truly showed off his flare for wisecracking comedy, as well as his nimble plotting abilities. Within three years Hayes was a top man in his field, with over 1,500 radio scripts to his credit. In a medium that relied on the spoken word, Hayes had become an expert in creating crisp, sophisticated dialogue.

It was during this period that Hayes met and courted Mildred Louise Hicks, a high-style fashion model, whose professional name was Mel Lawrence and whose beauty rivaled that of the most stunning leading ladies who would later appear in his films. They were married on August 29, 1950.

In 1951, Hayes caught the attention of Universal Pictures and was offered an opportunity to write for the movies. His first assignment was a World War II action film called Red Ball Express, which starred Jeff Chandler and Sidney Poitier. Hayes's next assignment at Universal was based on an original story of his own, which ultimately became Thunder Bay. It was his first of three scripts for James Stewart.

Following Thunder Bay, Hayes signed with the Music Corporation of America's talent agency, MCA Artists. Within days his new agent, Ned Brown, had gotten him assignments at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, including Torch Song, a Joan Crawford vehicle which marked her return to MGM after eleven years. A Jeff Chandler western, War Arrow, followed, as well as an adaptation of Richard Harding Davis's The Bar Sinister for MGM. (Production was held up until 1955, though, and The Bar Sinister was released in the U.S. as It's a Dog's Life.)

The move to MCA paid off, when in the spring of 1953 Hayes was handpicked by Alfred Hitchcock to adapt Cornell Woolrich's short story, Rear Window. The collaboration would be an important turning point for both. For Hitchcock, it marked the beginning of his most successful period, critically and commercially. For Hayes, it lifted him into the world of A-list directors, stars, and budgets, and began his long association with Paramount Pictures. Despite Hitchcock's reputation as a martinet, Hayes was given tremendous creative freedom, and together they created one of the most enduring works of the cinema.

Both he and Hitchcock earned Academy Award nominations for their work on Rear Window. Neither went home with Oscars, but Hayes did receive an Edgar award from the Mystery Writers of America for his screenplay. Their styles and temperaments meshed and Hayes went on to write Hitchcock's next three films - To Catch a Thief, The Trouble with Harry, and The Man Who Knew Too Much. But when Hayes successfully challenged Hitchcock over a credit dispute, the relationship came to an abrupt end.

Following his break with Hitchcock, Hayes was offered the job of adapting what was to become a scandalous bestseller, Grace Metalious's Peyton Place. Considered unfilmmable, Hayes tastefully reworked the novel's sensational elements into a sensitive drama that was a hit with audiences. Peyton Place became the top-grossing film of the year, and earned seven Academy Award nominations, including one for best picture, and one for Hayes's screenplay.

Adaptations of successful plays followed, including Thornton Wilder's The Matchmaker and But Not for Me, based on Samson Raphaelson's Accent on Youth. Hayes also worked uncredited on the Hecht-Hill-Lancaster film of Terence Rattigan's Separate Tables and on the Perlberg-Seaton film of Garson Kanin's The Rat Race. A number of popular novels Hayes adapted were not filmed.

As the 1950s drew to a close, Hayes grew disenchanted with Hollywood. The disappointment inherent in writing projects that were shelved or canceled; the pressures of working at a studio; the constant prodding by his agent that he should try his hand at directing; and prolonged negotiations between the WGA and producers over residuals helped Hayes make the decision to move with Mel and their children - Rochelle and Garrett - to Maine, where their youngest children, Meredyth and Corey, were born.

In spite of his being three thousand miles from Hollywood, offers continued to pour in. Hayes script-doctored an Elizabeth Taylor vehicle Butterfield 8 for MGM and followed with adaptations of Lillian Hellman's The Children's Hour, and Enid Bagnold's The Chalk Garden.

In 1962 Hayes began a long association with Joseph E. Levine. Having achieved notoriety for his company Embassy Pictures, through the distribution of foreign-made exploitation films, Levine decided to move into production and purchased the rights to Harold Robbins's steamy bestseller The Carpetbaggers. Hayes's adaptation was a tremendous financial success and was quickly followed by another Levine production of a Robbins novel, Where Love Has Gone. With the promise of greater control and financial compensation, Hayes entered a long-term contract with Levine which eventually led to his appointment as vice president in charge of literary properties for Embassy. What Hayes didn't know was that most of Levine's plans would never come to fruition, and many of the scripts he wrote for the company remained unproduced.

When Levine turned his attention to a bio-pic of Jean Harlow, he sacrificed quality for speed in a frantic rush to beat another Harlow production to the theaters. He called on Hayes to completely rewrite the script as it was being shot. After Harlow, Hayes took on another rewriting assignment, the Sophia Loren vehicle Judith.

Hayes's script Nevada Smith, based on the character from The Carpetbaggers, went into production in 1965 and would remain his last feature credit for nearly thirty years. (Hayes did write the cult hit Walking Tall, but opted not to accept screen credit.) In the 1970s, while still serving out his contract with Levine's Embassy Pictures, Hayes turned to writing and producing for television, including the TV movie, Winter Kill, and the pilot for a series based on Nevada Smith.

Hayes

continued writing into the 1980s, scripting Pancho Barnes, a

TV movie about the colorful life of the aviatrix, and coming close to

production on a number of other projects. One of these projects, Iron

Will, finally went before the cameras in the early 1990s. After

nearly thirty years, Hayes was once again in the spotlight.

Hayes

continued writing into the 1980s, scripting Pancho Barnes, a

TV movie about the colorful life of the aviatrix, and coming close to

production on a number of other projects. One of these projects, Iron

Will, finally went before the cameras in the early 1990s. After

nearly thirty years, Hayes was once again in the spotlight.

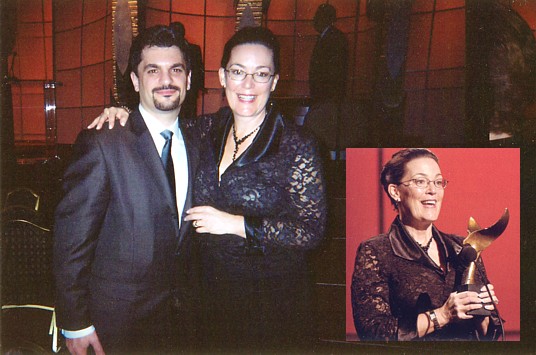

In recent years John Michael Hayes had been a professor of film studies and screenwriting at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, where he and Mel relocated in 1988. In addition, Hayes lectured around the country at film festivals and universities about his career. He officially retired in 2000.

In 2004, the Writers' Guild of America honored Hayes with its highest honor, the Screen Laurel Award. On November 19, 2008, John Michael Hayes passed away in Hanover, New Hampshire at the age of 89.